The last time I got tearful at an exhibition was The V&A’s Alexander McQueen show. Today at the new Tate Modern’s sensitively and sublimely curated exhibition of Georgia O’Keeffe’s work, it happened all over again. And then some.

The last time I got tearful at an exhibition was The V&A’s Alexander McQueen show. Today at the new Tate Modern’s sensitively and sublimely curated exhibition of Georgia O’Keeffe’s work, it happened all over again. And then some.

Rounding the corner of one of the first rooms I came face to face with ‘Music – Pink and Blue No. 1’. This was the catalogue cover of my first, and until this day, only viewing of Ms O’Keeffe’s art in the flesh as it were. That was in 1987, just a year after she died.

A flood of memories surfaced; living in New York and then Washington D.C. where the show had taken place at the National Gallery of Art. Tears pricked my eyes. Her powerful and confident strokes of both paint and charcoal reveal a determined character: Determined and dedicated to being true to herself.

In her own words, quoted on the introduction to each room in this exhibition she comes across as a woman of single mind and focus. I could say ‘person’ here, and many of the often cited quotes on her work refer to her as a great ‘woman’ painter which she famously railed against, saying ‘The men liked to put me down as the best woman painter. I think I’m one of the best painters’. However, only a female artist could say: ’Of course I was told it was an impossible idea – even the men hadn’t done that well with it’ on painting the New York landscape.

She knew she was up against it to be taken seriously as a woman who made art, and nothing less than 100% of herself would do.

Through showing such an extraordinary variety of her work in this exhibition, the Tate seeks primarily to champion O’Keeffe’s own insistence that her work was not overtly sexualised, that every flower and landscape she painted had little to do with sexuality and in particular the female body.

It’s largely succeeded in this mission, but there’s no getting away from the fact that there is an inherent sensuality and almost erotic like quality imbued within her paintings in particular – whether they be of New York skyscrapers or clouds floating beneath blue skies. Nature was such a source of inspiration to her, and that in its most basic form is reproduction – in all that is created.

The final rooms hosting her paintings from New Mexico stirred up emotion again. The ruthless and unrelenting desire to demonstrate clarity and one’s own truth is particularly piercing in the Pelvis series and the paintings of her Abiquiú house. The sense imparted is of an infinite search for oneself, to strip back all that doesn’t matter and reach the core: ‘I feel there is something unexplored about woman that only woman can explore’ she once said.

Her love of nature and the nature of love, in particular for oneself, is imbued in all Georgia O’Keeffe’s work. She just couldn’t help herself.

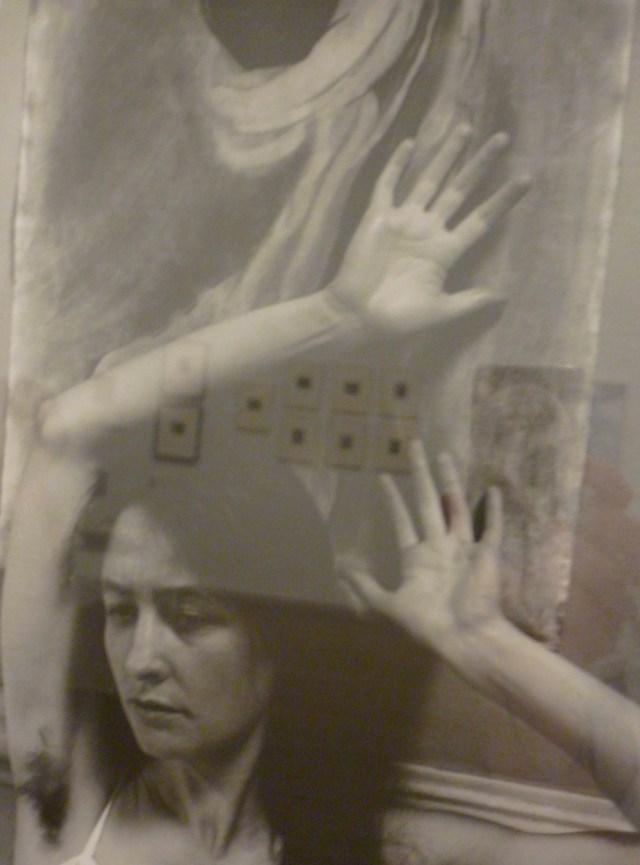

‘My Last Door’ Georgia O’Keeffe. Portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe by Alfred Stieglitz.

Georgia O’Keeffe at Tate Modern 6 July – 30 October 2016.

They informed me at the Press Office that I might be able to have a few words with Bjarke Ingels, architect of this year’s Serpentine Pavilion. I’d read about the unzipped wall and wondered how it would compare to past years’ structures.

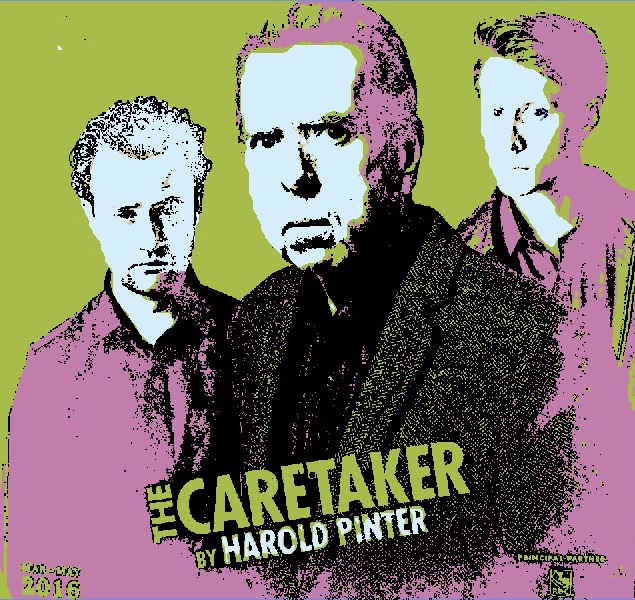

They informed me at the Press Office that I might be able to have a few words with Bjarke Ingels, architect of this year’s Serpentine Pavilion. I’d read about the unzipped wall and wondered how it would compare to past years’ structures. Pinter. Harold Pinter. The name says tension to me and a play fraught with awkwardness, strain, characters stretched to breaking point. I wasn’t sure I could handle a second one in as many months, but theatre invitations are rather lovely and it would be a hard woman that could say ‘no’.

Pinter. Harold Pinter. The name says tension to me and a play fraught with awkwardness, strain, characters stretched to breaking point. I wasn’t sure I could handle a second one in as many months, but theatre invitations are rather lovely and it would be a hard woman that could say ‘no’. I arrived five minutes early and asked the librarian where the writing group was meeting. She pointed to a corner where two elderly people sat – one reading the newspaper, another with a large stack of books indicating fervent research. “It starts at six thirty – right – until eight?” I asked.

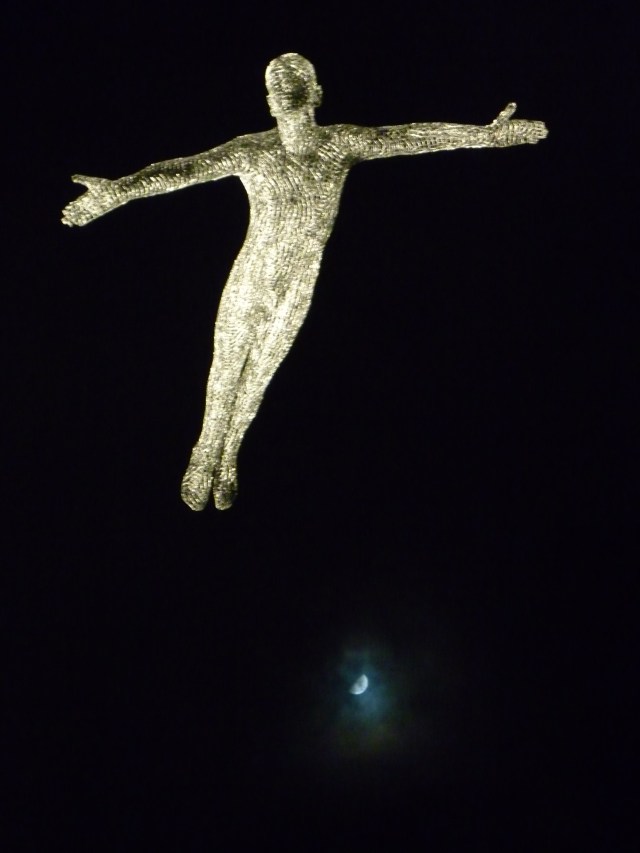

I arrived five minutes early and asked the librarian where the writing group was meeting. She pointed to a corner where two elderly people sat – one reading the newspaper, another with a large stack of books indicating fervent research. “It starts at six thirty – right – until eight?” I asked. Cold glittering pavements met my snow boot shod feet as I left the house. This was a night for adventurers, curious people, resilient Londoners. With a temperature of – 2 degrees layers were required to brave weather so freezing that it hurt ears, numbed hands and nipped consistently at already chilled faces. But oh, the reward.

Cold glittering pavements met my snow boot shod feet as I left the house. This was a night for adventurers, curious people, resilient Londoners. With a temperature of – 2 degrees layers were required to brave weather so freezing that it hurt ears, numbed hands and nipped consistently at already chilled faces. But oh, the reward.