“I’ve only just got it” explained the man in front of me at the end of Marina Tabassum’s talk on the 2025 Serpentine Pavilion. He was referring not to the pavilion she’s designed but rather his new ‘phone/camera which I’d had my eye on as he snapped away during the event. The lens seemed to be of an extraordinary quality rendering every image which appeared on the screen immaculate, pristine and of a clarity my eyes couldn’t quite believe.

I futilely brushed the lens of a now virtually vintage iphone 11 on my jeans and attempted to take a few more photos of where I was at: ‘A Capsule in Time’ a pill-like shaped temporary pavilion next to the old Serpentine gallery marking 25 years of like minded architecture. Except… this one is different – it moves.

Jordan and I studied the pavilion from a distance. “I’ve worked here for seven of these, and this is my favourite so far.”

“Why?” I asked.

“I love the colours, and it’s so grand. It also provides cover from the rain: if it’s pelting down like it did yesterday, that part moves very very slowly and closes eventually, offering shelter for more people. That wasn’t always the case, you know.” He said pointing to the far end, and the gap currently indicating fine weather.

I did indeed know about the rain element, recalling a time in 2016 when I’d visited Bjarke Ingels’ pavilion which, whilst beautiful to look at did not provide the practical element of shelter from storm.

Had the brief changed? And, if so, when?

Marina told us how she’d grown up in Dhaka; a privileged existence as the local doctor’s daughter, whilst living next to a slum. Her father served the local community and she wondered how she might do the same as an architect.

“How you build has to come from the land” she told us. “It’s important to go back to the beginning – to why something is, and why it is needed.”

She went on to cite the Khudi Bari structures she developed in the lockdowns of 2020: modular houses which can be moved due to their material components, they provide shelter for the marginalised landless population living in the sand beds of the river Meghna in Bangladesh.

“When there is flooding – people can live in the upper floor – or move their home.” Marina said. “I’m working with indefinite temporality in my architecture – and I hope it’s giving back – like my father did.”

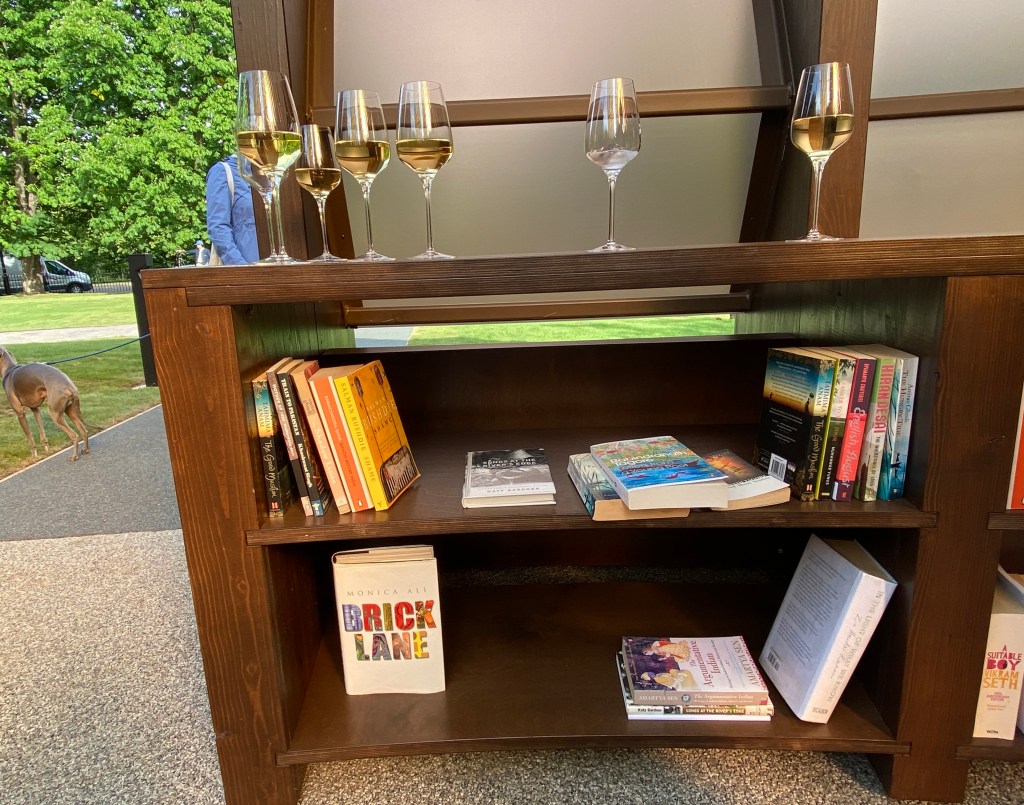

“On the other hand, this is definite temporality” she said, looking around at the now stained glass-like panels as the sun shone through: “the use changes over the next couple of months. It’s a time capsule and when it’s served its purpose here, I’d like its afterlife to be a library. In a time when education is being threatened by so many sources – we must protect it.”

The man in front of me pointed his acute lens at the various shelves currently home to some of Marina’s favourite books. Later, glasses of wine would be rested there before being cleared at the appointed hour for the evening’s next gathering.